Jigsaw

Six years ago four men robbed a bank. Then a shootout left them dead, and 750 grand missing. Now Detectives Carella and Brown are finding pieces of a photograph, each piece tied to a name, each name tied to a murder, each murder tied to the bank robbery six years ago. The 87th Precinct cops know than the complete picture will lead them to the money. They just don’t know how many people still have to die — before the last piece falls into place.

STEP RIGHT IN >>

Chapter 1

DETECTIVE ARTHUR BROWN DID NOT LIKE BEING CALLED BLACK.

This might have had something to do with his name, which was Brown. Or his color, which was also brown. Or it might have had something to do with the fact that when he was but a mere strip of a boy coming along in this fair city, the word “black” was usually linked alliteratively with the word “bastard.” He was now thirty-four years old and somewhat old-fashioned, he supposed, but he still considered the word derogatory, no matter how many civil rights leaders endorsed it. Brown didn’t need to seek identity in his color or in his soul. He searched for it in himself as a man, and usually found it there with ease.

He was six feet four inches, and he weighed two hundred and twenty pounds in his undershorts. He had the huge frame and powerful muscles of a heavyweight fighter, a square clean look emphasized by the way he wore his hair, clipped close, clinging to his skull like a soft black cap, a style he had favored even before it became fashionable to look “natural.” His eyes were brown, his nostrils were large, he had thick lips and thicker hands, and he wore a .38 Smith & Wesson in a shoulder holster under his jacket.

The two men lying on the floor at his feet were white. And dead.

One of them was wearing black shoes, blue socks, blue trousers, a pale blue shirt open at the throat, a tan poplin zippered jacket, a gold Star-of-David on a slender gold chain around his neck, and two bullet holes in his chest. The other one was dressed more elegantly: brown shoes, socks and trousers, white shirt, green tie, houndstooth-check sports jacket. The broken blade of a switch knife was barely visible in his throat, just below the Adam’s apple. A Luger was on the floor near his open right hand.

The apartment was a shambles.

It was not a great apartment to begin with; Brown had certainly seen better apartments, even in the ghetto where he had spent the first twenty-two years of his life. This one was on the third floor of a Culver Avenue tenement, two rooms and a bathroom, rear exposure, meaning that it faced on a back yard with clotheslines flapping Wednesday’s wash. It was now close to 10 p.m., six minutes after the building’s landlady had stopped the cop on the beat to say she had heard shots upstairs, four minutes after the patrolman had forced the door, found the stiffs, and called the station house. Brown, who had been catching, took the squeal.

The Homicide cops had not yet arrived, which was just as well. Brown could never understand the department regulation that made it mandatory for Homicide to check every damn murder committed in this city, though the case was invariably assigned to the precinct answering the call. He found most Homicide cops grisly and humorless. His wife, Caroline, was fond at telling him that he himself was not exactly a very comical fellow, but Brown assumed that was merely a case of the prophet going unappreciated in his native land. In fact, he thought he was hilarious at times. As now, for example, when he turned to the police photograph and said, “I wonder who did the interior decorating here.” The police photographer apparently shared Caroline Brown’s opinion. Without cracking a smile, he did his little dance around the two corpses, snapping, twisting for another angle, snapping again, shifting now to this side of the dead men, now to the other, while Brown waited for his laugh.

“I said. . .” Brown said.

“I heard you, , Artie,” the photographer said, and checked his camera again.

“This is certainly not the Taj Mahal,” Brown said.

“Hardly anything is,” the photographer answered.

“What are you so grumpy about?” Brown asked.

“Me? Grumpy? Who’s grumpy?”

“Nobody,” Brown said. He glanced at the corpses again and then walked to the far side of the room, where two windows overlooked the back yard. One of the windows was wide open. Brown checked the latch on it, and saw immediately, that it had been forced. Okay, he thought, that’s how one of them got in. I wonder which one. And I also wonder why. What did he expect to steal in this dump?

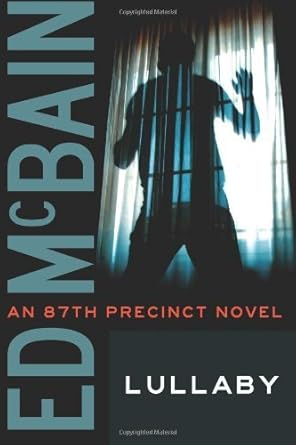

87th precinct books

Learn. more about selected 87th Precinct books and read the first chapter!

You can buy all 87th Precinct books now on Amazon >>